Syntax refers to the structure of language.

These structures are not objects that we can directly observe in the same way that we can hear the sound of a word or see the shape of a hand sign.

Nevertheless, we can find evidence that such syntactic structures exist in our minds.

Do sentences have structure?

In a way, it’s obvious that sentences have some kind of structure.

Words in a sentence are uttered in a certain order. The order of words in (1) and (2) makes the difference between sense and nonsense.

(1)

Time flies like an arrow.

(2)

*Arrow an like flies time.

So it seems clear enough that sentences must have at least one-dimensional or linear structure, like beads on a string.

But there is evidence to believe that sentences have two-dimensional or hierarchical structure.

Do sentences have hierarchical structures?

Consider the following sentence.

(3)

John saw the man with a telescope.

This sentence is ambiguous:

- It could mean that John saw the man who had a telescope.

- Or it could mean that John saw the man by using a telescope as an instrument.

How is it possible that a single string of words can have two different meanings?

One explanation is that these two meanings correspond to different structures.

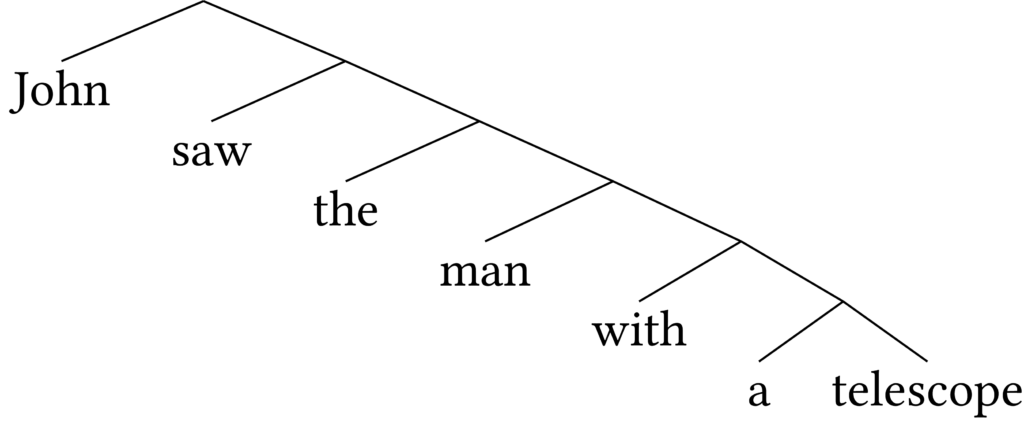

The first reading corresponds to the structure in (4).

(4)

In this structure, with a telescope composes with man. Thus, with a telescope specifies the kind of man that John saw (i.e., a man with a telescope}.

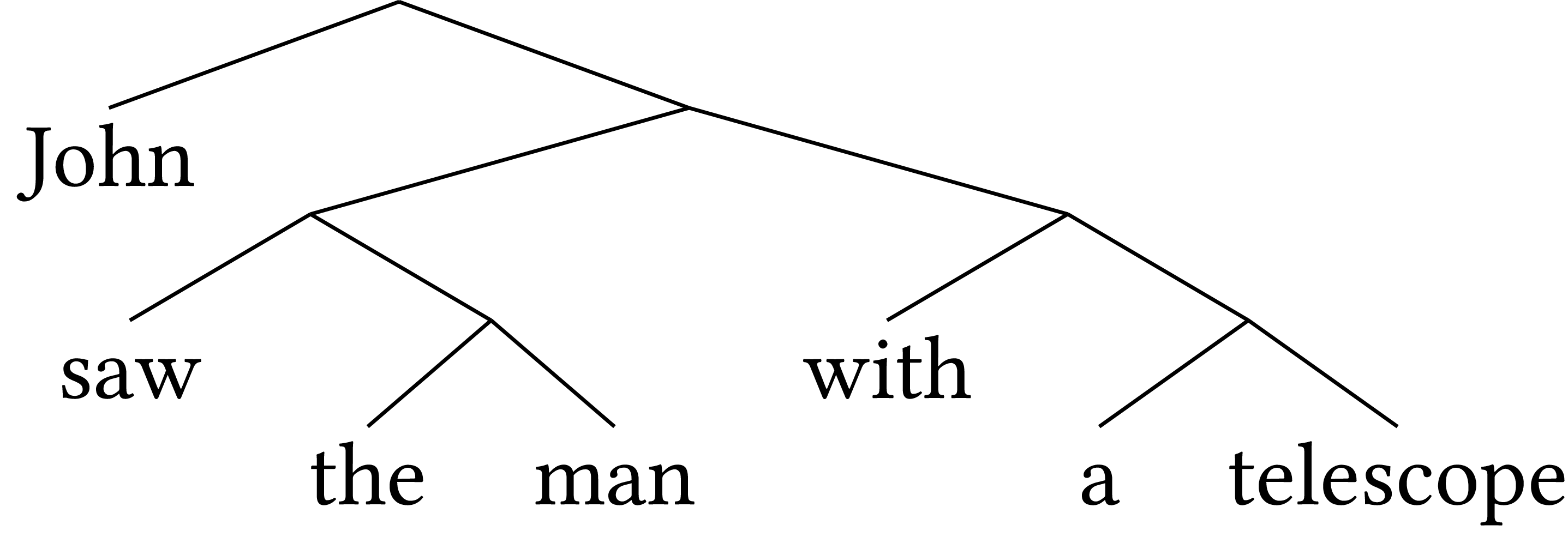

The second reading corresponds to the structure in (5).

(5)

In this structure, with a telescope composes with saw the man. Thus, with a telescope modifies the event of seeing.

Ambiguous readings like these are described as structural ambiguities, because each reading corresponds to a distinct structure.

Structural ambiguity provides evidence for the existence of structure in the way our minds represent sentence.

Do words have hierarchical structures?

Even the words that make up a sentence can have hierarchical structures of their own.

Consider the word unfoldable: un– + fold + –able.

Now consider the meaning of unfoldable in the following sentence.

(6)

This bag is unfoldable.

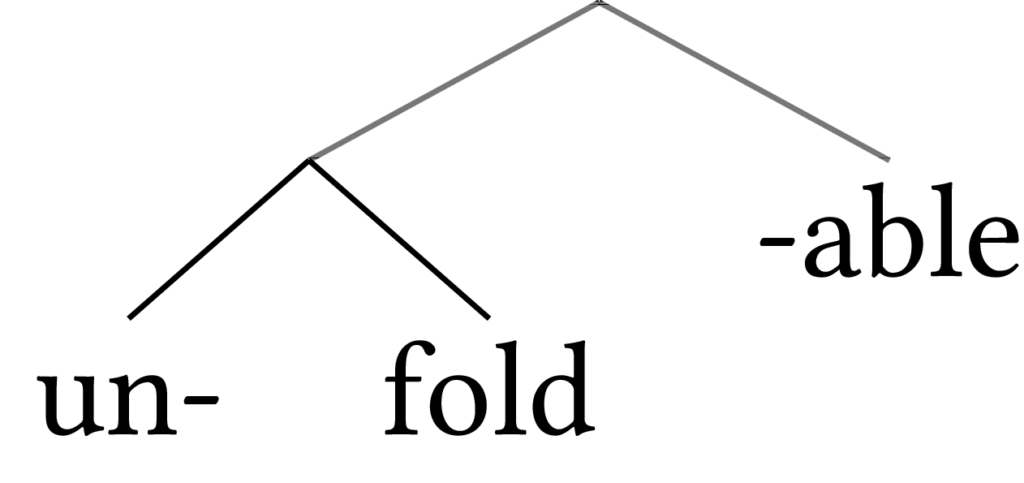

On the one hand, (6) could mean that the bag can be unfolded (e.g. into a larger bag). In this case, unfoldable would have the structure as in (7).

(7)

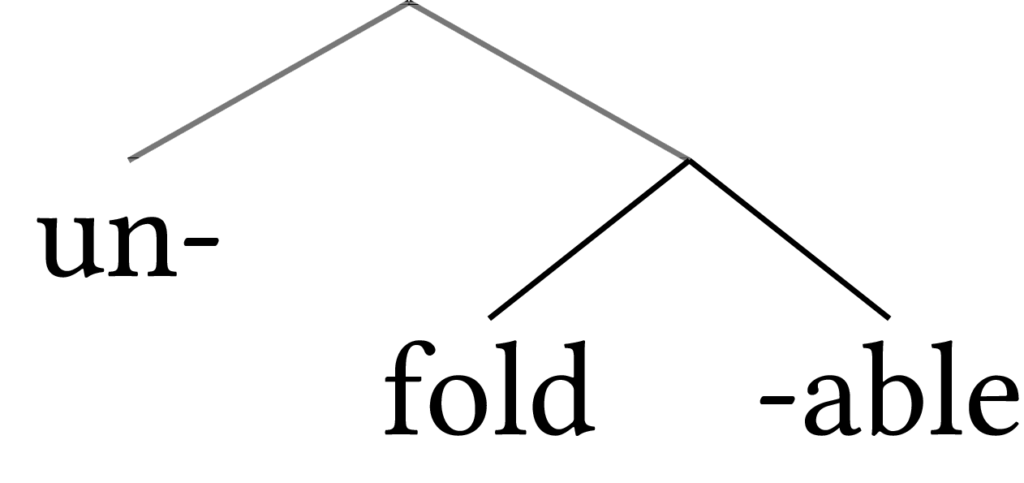

On the other hand, (6) could mean that the bag cannot be folded (e.g. because the fabric is too stiff). In this case, unfoldable would have the structure as in (8).

(8)

The part of language responsible for putting together the structure of words is called morphology.

Syntax all the way down?

A big debate among syntacticians is the relation between syntax and morphology.

Some syntacticians think that it doesn’t make sense to make a distinction between the part of syntax that builds sentences and the part that builds words. Why have two structure-building systems when you can have just one?

Other syntacticians think that syntax and morphology are distinct systems because they have different properties and operate based on different rules.

In my research, I show that a certain construction known as resultatives have different properties when they are built in syntax as compared to when they are built in morphology.